Analytic Tradecraft Standards - A Practitioner’s Guide to ATS & Application

Introducing Analytic Tradecraft Standards:

Intelligence Community Directive 203 (ICD-203) designates the standards for the production and evaluation of analytical products developed by U.S. Intelligence Community (USIC) personnel. Further, it outlines the responsibilities of intelligence analysts to pursue excellence, integrity, and rigor in their analytic thinking and work practices.

While ICD-203 only directly applies to all entities within the USIC, ICD-203 serves as best-practices and remain applicable for intelligence and law enforcement professionals within the U.S. domestic intelligence apparatus (i.e., U.S. state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) law enforcement, as well as the Fusion Center Network). Following the analytic standards set forth in this directive also helps improve civilian analytical assessments.

The directive delineates five USIC Analytic Standards and nine Analytic Tradecraft Standards (ATS)from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI):

Analytic Standards:

Objectivity – Intelligence analysts are required to perform and assess with objectivity and awareness of their own assumptions and reasoning. To do so, analysts engage in practical techniques to reveal and mitigate underlying biases. A core prerequisite to objectivity is caution against unduly constraining new developments with prior judgements.

Independence of Political Consideration – Analytic assessments are susceptible to distortion or shaping from advocacy of the audience/consumer, agendas, or policy viewpoints. Analytic judgements must not be influenced by the force or preference for specific policies.

Timeliness – Analysis must be produced and disseminated in time for it to be actionable by customers. Intelligence analysis is written for decision makers and policy makers. Consider your audience, their schedules and timelines along with the intelligence requirements established to produce timely intelligence.

Exploitation of All Available Sources of Information – Analysis should always be informed by all relevant information available. Analytic elements must identify and address critical information gaps and simultaneously work with collectors to develop information access and collection strategies.

Adherence to ATS.

Analytic Tradecraft Standards (ATS):

Properly describe the quality and credibility of underlying sources, data, and methodologies.

Properly express and explain uncertainties associated with major analytic judgements and assessments.

Properly Distinguish between underlying intelligence information and analysts’ assumptions and judgements.

Incorporate analysis of alternatives.

Demonstrate customer/audience relevance, salience, and address implications.

Use clear and logical argumentation.

Explain changes to or consistency of analytic judgements and assessments.

Make accurate judgements and assessments.

Incorporate effective visual information where appropriate.

Understanding & Practical Application of ATS

ATS 1: Quality and Credibility of Underlying Sources, Data and Methodologies

Intelligence analysis must properly describe the quality and credibility of underlying sources, data, and methodologies.

Intelligence analysts must clearly express the sources and collection methods underpinning their analytic judgements and assessment. This is critical in ensuring intelligence consumers and decisionmakers understand the evidentiary foundation of the product and enables transparency.

Per ICD-206, the directive establishing the requirements for sourcing information disseminated in analytical products, analysts are expected to apply source descriptors capturing:

Accuracy & Completeness – How reliable is the information? Is the information partial or complete?

Denial & Deception – Are there adversarial efforts to manipulate, obscure, or falsify information?

Relevance & Timeliness – Is the information outdated? If the information still relevant? Is there more current information available?

Technical Considerations – Are there limitations or strengths of the platforms or systems used (i.e., image resolution for IMINT, intercept quality for SIGINT).

Source Attributes – What is the access of the source to the desired information? Has the information been validated? Are there underlying motivations or biases from the information source? Does the source have specific expertise?

NOTE: law enforcement sensitive and classified sources require additional sensitivity when writing source summary statements.

ATS 2: Expressing and Explaining Uncertainties

Intelligence analysis must properly express and explain the uncertainties associated with major analytic judgements and assessments.

This component of ATS is two-part: (i) Intelligence analysts need to both explain the likelihood of their analytic judgement or assessment and their confidence level in the judgement; as well as (ii) explicitly define uncertainties concerning their assessment and judgement.

Expressions of Likelihood & Confidence Levels

In analytic writing and intelligence, phrases like “judge” and “assess,” and terms such as “likely” and “probably” convey analytical judgements and assessments. Terms of likelihood range across a full spectrum from ‘almost no chance’ to ‘almost certain’. Terms of probability range from ‘remote’ to nearly certain’.

NOTE: Intelligence analysts should avoid dealing with absolutes as threat reporting and analysis will rarely provide enough depth, perspectives, and evidence to determine certainty on either end of the spectrum. Terms like ‘no chance’ and ‘certain’ that would indicate a 0% or 100% chance are not compatible with analytic assessments. A certain level of uncertainty and unknowns are inherent to the intelligence process. Additionally, analysts must refrain from mixing terms of likelihood with terms of probability in the same product.

The following chart breaks down likelihood and probability levels defined by the ICD-203:

Differing from terms of likelihood and probability, Confidence levels are tied to the logic, evidence, and understanding underlying the judgements. Confidence levels are specifically derived from quantity and quality of sources, strength and corroboration of sources, and an analyst’s expertise.

Below is a breakdown of confidence levels used for ECHO Intelligence products, which readers are encouraged to integrate or rework for the purposes of their own assessments. Confidence levels and definitions should remain consistent across an agency or network (i.e., fusion center network).

ECHO Intelligence Confidence Levels:

High Confidence - Indicates that analytical judgements are based on robust and high-quality information, or that the nature of the issue allows for solid assessment. While additional reporting information sources may change the analytical assessment(s), these changes are likely to be refinements rather than substantive alterations to the assessment(s).

Medium Confidence – Indicates that the information available can be interpreted in various ways, that ECHO has alternative views, or that the information is credible and plausible, but not corroborated sufficiently to warrant a higher level of confidence. Additional reporting or information sources can increase confidence levels or substantively alter the analytical assessment(s).

Low Confidence – Indicates that the information used to make the analytical assessment(s) is sparse, questionable, or fragmented to the point where solid analytical inferences are difficult to make, or that ECHO has significant concerns. Absent additional reporting or information sources, analytical assessment(s) with low confidence are preliminary in nature.

Explaining Uncertainty

Analytic uncertainty can be caused by numerous things, including but not limited to (i) type, recency, and the amount of available information, (ii) known knowledge gaps, the (iii) complexity or ambiguity of the issue, and (iv) reliance on assumptions or use of untested models.

Intelligence analysts should always explain the impact of uncertainty; clarifying to what degree the analytic line depends on assumptions and explicitly stating where judgements are contingent or provisional. This explanation should, as appropriate, highlight the observable events, collections, or reporting that would increase or decrease uncertainty related to the analytic judgement or assessment.

Implementation of explanations of uncertainty can be found in various forms within intelligence products dependent on the authoring agency. However, ECHO advocates for these explanations to be included within the executive summary of a product as standard practice.

ATS 3: Distinguishing Between Information, Assumptions, and Judgements

Properly distinguish between underlying intelligence information and analysts’ assumptions and judgements.

Intelligence analysis should differentiate underlying intelligence information (i.e., facts, source information, data, law enforcement reporting), assumptions (suppositions inherently used to frame arguments or bridge gaps), and judgements (conclusion drawn from information, analysis, and assumptions).

When central to the judgement or assessment (i.e., “linchpins”), assumptions must be explicitly stated. It is critical to state any assumptions when they compensate for critical gaps. Judgements are presented as conclusions based on available evidence, analysis, and the assumptions noted in the product and must be distinguished from factual reporting. For the purposes of written intelligence products, the analytic judgement or assessment should be clearly written and bolded within the executive summary.

A simple way to ensure adherence to ATS 1-3 is to follow the following outline for written intelligence products:

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Judgement/Assessment in full (one sentence)

Concise source breakdown (1-3 sentences)

Statement of confidence (one sentence)

Key assumptions breakdown (1-3 sentences, define at least two ‘linchpin’ assumptions.

Define indicators (2-4 sentences)

SOURCE SUMMARY STATEMENT

SUBSTANTIATION/EVIDENCE SECTION

WHAT of the product which lays out sourced evidence.

(ADDITIONAL OUTLINING AVAILABLE IN TEMPLATE DOC FOR REMAINING COMPONENTS)

ATS 4: Analyzing Alternatives

Incorporate analyses of alternatives.

The Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) is a critical component of a robust written intelligence product and should be incorporated alongside any analytic assessment or judgement. Analysis of alternatives functions to explain events/phenomena, explore near-term outcomes, and envision possible futures to mitigate surprise and risk.

Analysis of alternatives are most impactful when (i) major analytic judgements and assessments face significant uncertainty, when (ii) issues assessed are highly complex (i.e., any forecasting analysis), and (iii) when black swan events could significantly reshape outcomes. The section must identify and assess plausible alternative hypotheses, discuss the assumptions, likelihoods, and implications for consumer interests, and identify indicators that, if observed, would shift the likelihood of defined alternatives.

Inclusion of analysis of alternatives should be standard for intelligence production and not something included only in exceptional situations. Within guidance for adherence to ATS, the ODNI notes that “dissenting views count as alternatives.”

Integrating AoAs Made Easy:

An AoA is never an afterthought to an intelligence product. Identifying alternatives early in the analytic process is a fantastic way to add analytic rigor to your process. ECHO recommends employing Structured Analytic Techniques (SATs) like Analysis of Competing Hypotheses or Multiple Scenario Generation after evidence and information supporting the production of intelligence. Additional ECHO-authored guidance and resources for SATs is available.

ATS 5: Relevance and Implications for Consumers

Demonstrate consumer relevance and address implications.

Whether written for policymakers, law enforcement, field operators, military personnel, or the public; intelligence analysis needs to be tailored to the specific needs of the consumer. Products must not simply relay or regurgitate information but provide explanation into what the information means – i.e., consider what the information means and its implications for decision, policies, operations, or strategies.

Intelligence products should go beyond mere description by providing prospects (likely outcomes or scenarios), context (background or framing to aid consumers in developing baseline understanding of situations and salience), threats (relative to risk, adversarial action, or vulnerabilities), and opportunities for action (windows where the consumer could intervene or exploit developments). Remember, all good intelligence analysis is actionable from a tactical, operational, or strategic consumer standpoint. If a product does not answer the “So what?” question for the intended consumer, more work is required.

Intelligence analysts should ask themselves the following questions to ensure adherence to ATS 5:

Does this product address the defined consumer’s mission, authorities, and interests?

Does this product explain why the issue matters?

Are consumer implications explicitly stated instead of inferred?

ATS 6: Clear and Logical Argumentation

Use clear and logical argumentation.

Every written intelligence product must present a singular, clear analytic message upfront–a BLUF (Bottom Line Upfront). An analytic best practice is to start an intelligence product with the BLUF. If a product includes multiple analytical judgments or assessments (i.e., an annual state/national threat assessment), they must collectively support a unified, overarching message.

The following questions can help guide intelligence analysts in the drafting and initial review process to ensure adherence to ATS 6:

Does this product have a single, clear analytic message (key analytic judgement or assessment) up front?

If the product has multiple judgments or assessments, are they collectively supporting a unified overarching message? What is the message they support?

Are all judgements and assessments properly grounded and supported with relevant intelligence information?

Is the language and syntax of the product precise? Is there any ambiguity in the diction? Are there vague terms or phrases present in the draft that could confuse consumers or be misinterpreted by readers?

At any point, does the draft or sections therein contradict itself or the judgments?

Does this product acknowledge both supporting and contrary information affecting the judgment?

Can the reader identify the main message (i.e., key judgement or assessment, overarching analytic message) within 30 seconds of reading the product?

ATS 7: Explain Change and Consistency

Explains change to or consistency of analytic judgements.

Finished intelligence products represent the analytic judgment of an agency at a specific moment in time—a snapshot shaped by the information available when written. Because new reporting is constantly collected, exploited, and analyzed, these judgments often require updates or revisions. For example, an annual statewide threat assessment may retain much of its core language and identified threats, but changes will emerge as the threat environment evolves, adversaries adopt

new tactics, techniques, and procedures, or as state and federal policy priorities shift.

ANALYST NOTE: For intelligence products, analysts should clearly state whether the key analytic judgements or assessments are (i) consistent with prior analysis, (ii) a shift from previous judgements, or (iii) delineate when providing a background in initial analysis of a subject. These explicit expressions need not be lengthy, and should avoid ‘boilerplate language’ (i.e., “there has been no change since the last report”). Instead, the expressions should convey what new information or analytical reasoning has prompted the noted changes and what consistency (if any) remains appropriate.

For recurrent products (i.e., daily updates/SITREPs), intelligence analysts should always note changes in the judgments. Should no changes be present, consistency need not be restated.

NOTE: If your product differs from the judgments and assessments of other elements within the USIC, acknowledge those differences and bring them to the forefront of your consumer’s attention.

ATS 8: Accuracy

Make accurate judgements and assessments.

This ATS is inherently the most difficult for supervisors and analysts to ‘grade.’ Much of this ATS falls upon supervisors and oversight entities (i.e., ODNI) to ensure and review adherence.

For intelligence analysts, accurate judgments are made possible by applying subject matter expertise and sound reasoning to all available information and known gaps at the time of writing. Intelligence analysts have a responsibility to present judgements and assessments that are accurate based on current information and analysis, useful, and actionable for the consumer(s). Avoiding making judgments to minimize the risk of being wrong does nothing to support action and ultimately benefits consumers.

While accuracy inherently relies on the clarity and logic of ATS 2 and 6, it also depends on the customer's ability to interpret the analytic message of the product as intended. Miscommunication in writing undermines accuracy as much as analytical or factual errors. To mitigate miscommunication, address:

The likelihood or probability of an occurrence or situation;

The underlying support evidence supporting the analytic judgement(s);

The timing of when an event or outcome is expected;

The nature of what specifically will happen, not vague generalities.

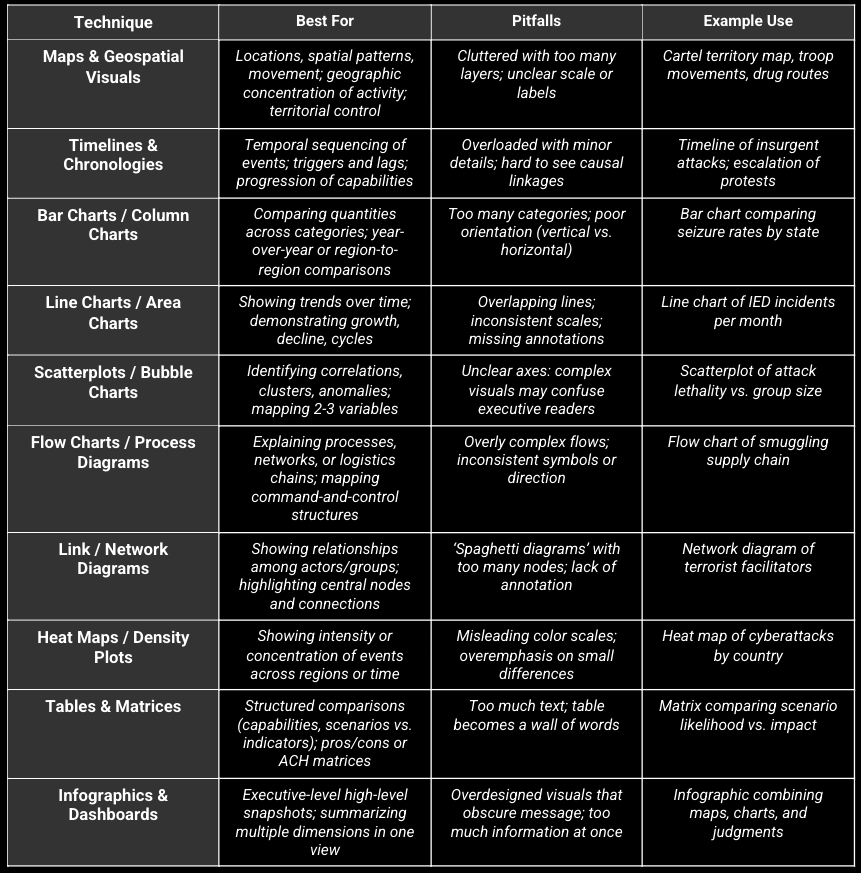

ATS 9: Effective Visuals

Incorporate effective visual information where appropriate.

Contrary to popular belief, visuals are not optional add-ons; they’re a core instrument within an analytic toolbox to aid in conveying complex information rather than relying on text alone. However, their use requires the same rigor and clarity as the written text of an intelligence product. Additionally, visual aids should never be viewed as ‘throw-away’ graphics to placate an ATS. Each should be impactful.

Visuals are beneficial when information involves spatial or temporal relationships (e.g., maps, timelines) or when complex information can be made visually comprehensible (e.g., flowcharts, link charts, structured datasets). ECHO notes that, at times, intelligence analysts may better convey written data with visual graphics that supplement and support written descriptions than text alone.

NOTE: Visual analytic content is subject to the same ATS as written content. Avoid inclusion of visuals simply for the sake of aesthetics or shock value. Always assess what a visual provides to the overall intelligence product. Should that assessment prove challenging, consider whether the visual should be excluded or revised.

Examples techniques, use applications, common pitfalls, and example applications can be found in the chart below: